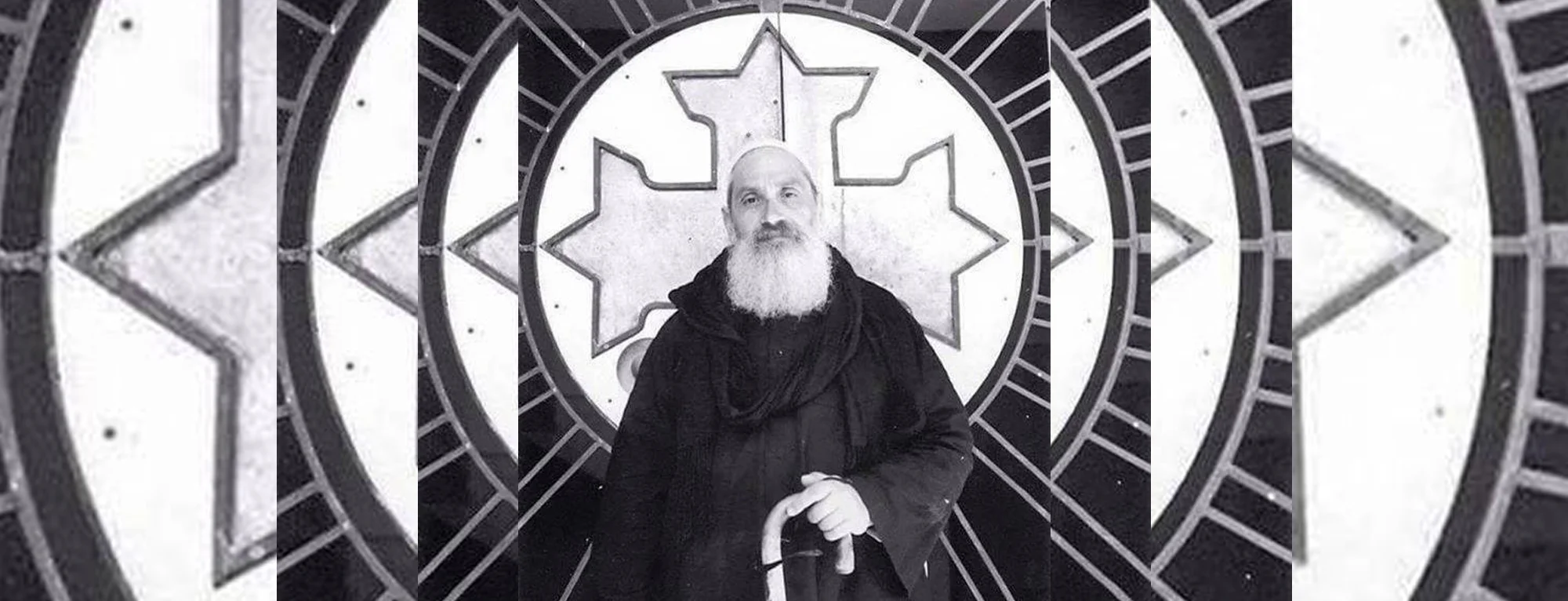

Father Matthew the Poor (1919 – 2006)

( Arabic: متى المسكين )

Was a saintly Coptic monk, a Christian thinker and a great scholar.

His reviving influence upon Coptic monasticism is felt worldwide. He carried the torch of spiritual and theological enlightenment in the church by combining fundamental teachings with the needs of modern thinking. By doing this he transformed the monastic life from that of simple, undereducated and less-religious worshippers to a life for the more serious seekers of the truth.

The spiritual father of Egypt’s St Macarius Monastery (Abu Maqar), the hegoumen Matta Al-Meskeen (Matthew the Poor)

His life in brief:

• Born, Yousef Iskandar, in Benha a town 45km north of Cairo in 1919.

•He graduated with a degree in pharmacy in 1944. He worked as a pharmacist till 1948.

•Following the Lord’s call, he sold everything he owned, and, except for the price of a one way ticket to the monastery, he distributed his wealth amongst the poor.

•On August 10, 1948, he became a monk in the monastery of his choice, the poorest of them all, the monastery of Anba Samuel in Upper Egypt.

•At Anba Samuel he spent his nights reading the Bible with great diligence until morning prayers. He started writing his first book Orthodox Life of Prayer.

•He was forced to move to El-Surian Monastery in Wadi Al-Natroun in 1951. There he was ordained a priest.

•He lived a solitary life at a fair distance from the monastery. After two years, Abouna Matta was asked to be the spiritual father of the monastery’s monks particularly the young among them.

•He became around that time the founder of the revival of Coptic monastic life. He returned monasticism to its glorious days by reviving the spirit of the great fathers of the desert, becoming a leading example of the highest level, and showing great talent in matters of fatherhood and planning—things that were missed since the days of fourth century fathers. This attracted many educated Christian youths around him to be given the right guidance in a modern monastic community.

•There, at El-Surian, he finished his first book, Orthodox Life of Prayer, first published in 1952 and again in 1968 with corrections and additions. Orthodox Life of Prayer was later translated into French (1977), Italian (1998), English (2002), and German (2007).

•In 1954 Pope Anba Yousab II, Patriarch of Alexandria, appointed him a deputy on the Parish of Alexandria after elevating his clerical rank to hegoumen. Abouna Matta stayed in this position for two years. On leaving he left behind a deep spiritual impression on many among the clergy of the region which is still felt by the Christian community at large until the present day.

•At the beginning of 1955 he chose to return to the life of serenity in the desert, returning to El-Surian Monastery.

•In mid-1956, he left El-Surian Monastery and returned to the monastery of Anba Samuel, seeking greater solitude.

•In 1969, Pope Kyrillos called Abouna Matta and his disciple monks to move to the monastery of Abu Maqar (St. Macarius), situated halfway between Cairo and Alexandria in Wadi Al-Natroun. Upon arrival, the monks found the fourth century monastery in ruin. It was occupied by only five elderly and sick monks, and the structures within the monastery were at the point of collapse.

•From that time, a great revival within the monastery occurred, both in spirit and in construction. Today, in 2006, there are 130 monks and the area of the monastery itself is six times the original size, in addition to a great land around the monastery, planted by the monks. Abo Maqar is a pilgrimage for many from all over the world.

•At Abu Maqar, Abouna Matta penned many books that are still in use by the Christians in Egypt and in the Middle East, and many are translated in foreign languages. He wrote 180 books, in addition to many journal articles (about 300).

•On April 2000, he founded Archangel Michael Coptic Care for the relief of the poorest Coptic families in Egypt.

•Even on his death bed, Abouna Matta Al-Meskeen, at the age of 87, kept writing. The last of his works is a series of booklets titled With Christ. These are works of contemplation on the gospels, and have soon appeared in three volumes in Arabic and many are translated into English in St Mark Review.